Reid Gladman, a recent Queen’s University graduate, remembers telling his parents that he was pretty sure he had a brain tumor after experiencing his first seizure in grade nine. Following an MRI in his hometown of Kamloops, British Columbia showed no evidence of a tumor, and after experiencing subsequent seizures, he was diagnosed with idiopathic epilepsy, the type for which doctors cannot pinpoint an apparent cause.

Fast forward almost eight years, and following one of the worst seizures Gladman’s ever had, another MRI was ordered, this time in Kingston by Dr. Lysa Lomax, neurologist and director of Kingston Health Sciences Centre’s (KHSC) District Epilepsy Centre. Using images from KHSC’s new 3-Tesla MRI machine, a neuroradiologist detected a cavernoma, a cluster of abnormal blood vessels, located in one of the temporal lobes of Gladman’s brain.

Knowing what was causing the focal seizures, which are disruptions of electrical impulses in a specific part of the brain, was a kind of relief for Gladman. “It didn’t exactly scare me to learn I had a type of non-cancerous brain tumor,” says Gladman. “Over the years, I had tried a variety of anti-seizure drugs, which would work for a while and then stop working. This new information meant there was a possibility of treating the seizures in a different way.”

Surgery is potentially possible in 50 per cent of people, like Gladman, who have not been able to control the focal seizures they experience after trying two or more anti-seizure medications.

The decision to recommend surgery is made by a multidisciplinary team that includes neurologists, neurosurgeons, nursing, social work, neuroradiologists, and neuropsychologists, who assess learning and memory function and ensure that brain function remains intact after surgery.

Before Gladman’s surgery could be scheduled, he was admitted to KHSC’s Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) for pre-surgical evaluation. After several days of prolonged electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring (five to 14 days) by a technologist, Dr. Garima Shukla identified the nature and location of his seizures. She, along with Dr. Gavin Winston and Dr. Lomax, is one of three epileptologists who carefully review EEGs at KHSC.

“I’ve spent many years trying to control the seizures, so to be in the hospital hoping to have a seizure that could be examined was an odd feeling,” says Gladman. “Any uneasiness I was feeling was quickly settled thanks to the extra effort staff, especially the technologist Tim Woodford, made to explain everything to me and keep me company.”

Recently, a patient admitted to the EMU wrote to say, “The EMU staff were the most caring people I have ever met.” Yet another patient had this to say, “Thank you for the exceptional health care I received during my stay in the EMU. As a nurse, it brings me great joy to see health-care members work so well individually, and together as a team.”

Since expanding three years ago, the EMU now monitors up to 155 patients a year and often completes four pre-surgical assessments a week. “This is the definition of patient-centered care,” says Dr. Lomax. “Patients no longer have to travel to Toronto, London or Montréal, which are all excellent epilepsy centres, at high cost to see health-care professionals with whom they are not familiar, to undergo stressful investigations and procedures.”

Gladman, who doesn’t drive because of his seizures, agrees. For many, travelling that distance may require them to take public transportation alone. Travelling on his own is not something Gladman makes a habit of doing. “I had a seizure once on a shuttle bus in Toronto on my way to meet a friend; I was alone, and I didn’t get a chance to tell any of the strangers on the bus that I was going to have a seizure.” Thanks to his medical alert bracelet, he was able to get the support he needed.

Driving is something Gladman is looking forward to doing again. The last time he was able to drive was when one of the medications was working for a two-year period about four years ago.

Last August, Gladman had brain surgery to remove the cavernoma. He was discharged from hospital after 24 hours and had only a headache for a short time. The two neurosurgeons with expertise in epilepsy surgery at KHSC are Dr. Faisal Haji and Dr. Ron Levy.

Gladman has been seizure-free for almost a year. He is back home and has been back on the road driving for a couple months, after receiving the approval to do so from his neurologist in B.C.

Epilepsy is a life-changing condition; and because of the associated limitations, people who live with it tend to experience higher than average levels of depression or anxiety. Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological conditions – second most common to headaches. One in 100 people live with some form of epilepsy. It is often defined as having two or more unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart.

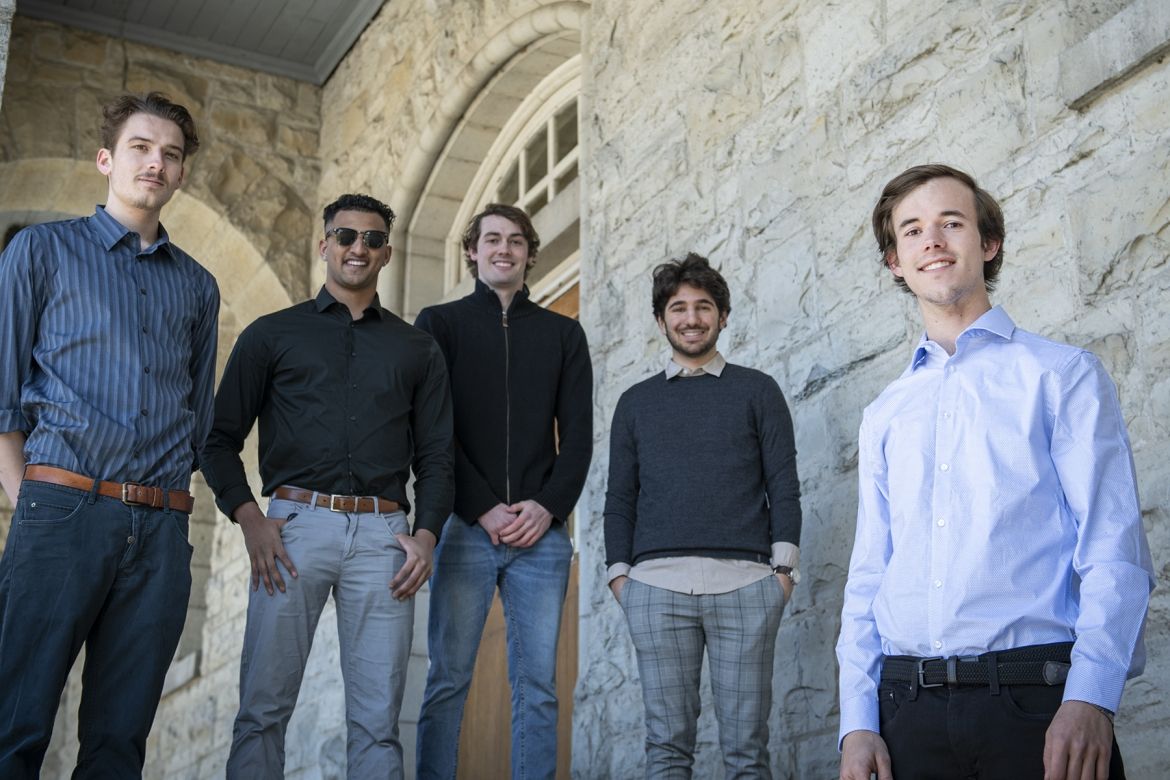

Gallery

Before having epilepsy surgery last August and being seizure-free ever since, Reid Gladman (foreground) says he looked to his roommates for support when he was having seizures regularly. He learned that it was more important to tell someone he was having