For years, patients with unexplained bleeding disorders have faced long, frustrating journeys. Many go months or years without a diagnosis, and some never get conclusive results.

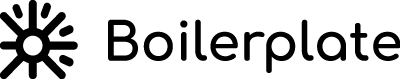

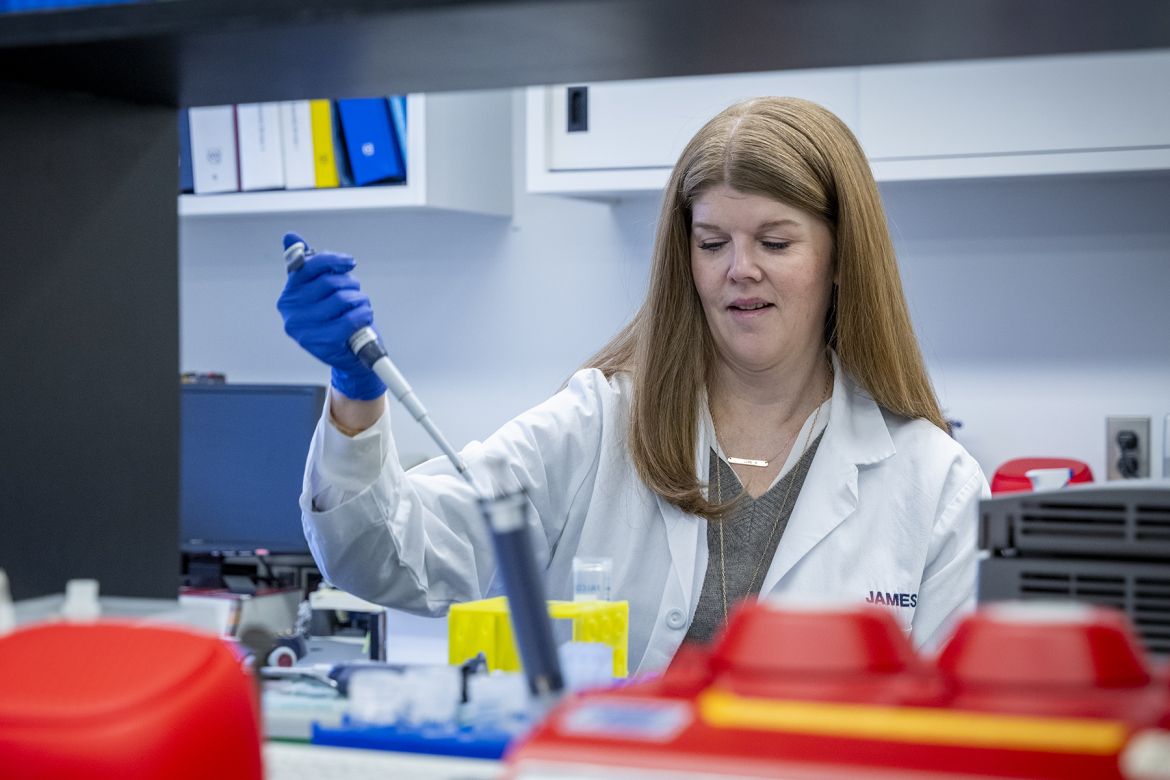

A new study, led by Dr. Paula James, a hematologist at Kingston Health Sciences Centre (KHSC) is hoping to change that.

One of the things that keeps me up at night, is thinking about the people out there with an undiagnosed bleeding disorder. You get in a car accident or need unplanned surgery, and complications arise that could’ve been prevented. With bleeding disorders, it’s better to prevent than treat it, because once the bleeding starts, you’re already behind the gun.

Standard lab tests can confirm a bleeding disorder about 30 to 40 per cent of the time, and usually within a few weeks, but that still leaves a large portion of people waiting for answers. The hope is that genomic sequencing – testing that looks at a patient’s actual genes – can help close that gap.

Patients in the study are split into two groups: one gets whole genome testing, looking at hundreds of genes linked to blood clotting and platelet function. The other group gets standard lab testing.

The results so far are promising.

“We’re seeing that 20–30 per cent of the time, genomic testing gives results beyond what we’d get from standard lab tests,” says Dr. James. “For patients who would otherwise remain undiagnosed, it can make a huge difference.”

The team is halfway through the study, and patients have been enthusiastic and generous participants.

“For many, this is the possibility of answers after years of uncertainty,” says Dr. James. “And for families, it can change the course of their health story, since many of these disorders are inherited.”

Addressing the equity gap in care

Men’s bleeding is often obvious - into muscles or joints - making irregular bleeding easier to diagnose. Menstrual bleeding, on the other hand, is a normal process, so it’s harder to know when a heavier period is indicative of a bleeding disorder.

There’s a different kind of suffering: psychological and social. Women with heavy periods who are out for weeks because of severe bleeding or people who battle chronic lethargy because of an iron deficiency.

Fatigue and iron deficiency can affect work, school, parenting, and daily life. Many people can go their whole lives wondering why they feel this way. A bleeding disorder is possible, but can be hard to clearly diagnose.

You give someone IV iron and their periods get better—you’ve just changed their life. Our hope is that one day, genomic testing will be available to anyone who needs it, so no one has to wait years for answers.

Dr. James has developed a self-administered bleeding assessment online tool that will help people better understand their bleeding and guide them toward the help they need. Visit www.letstalkperiod.ca for more information.

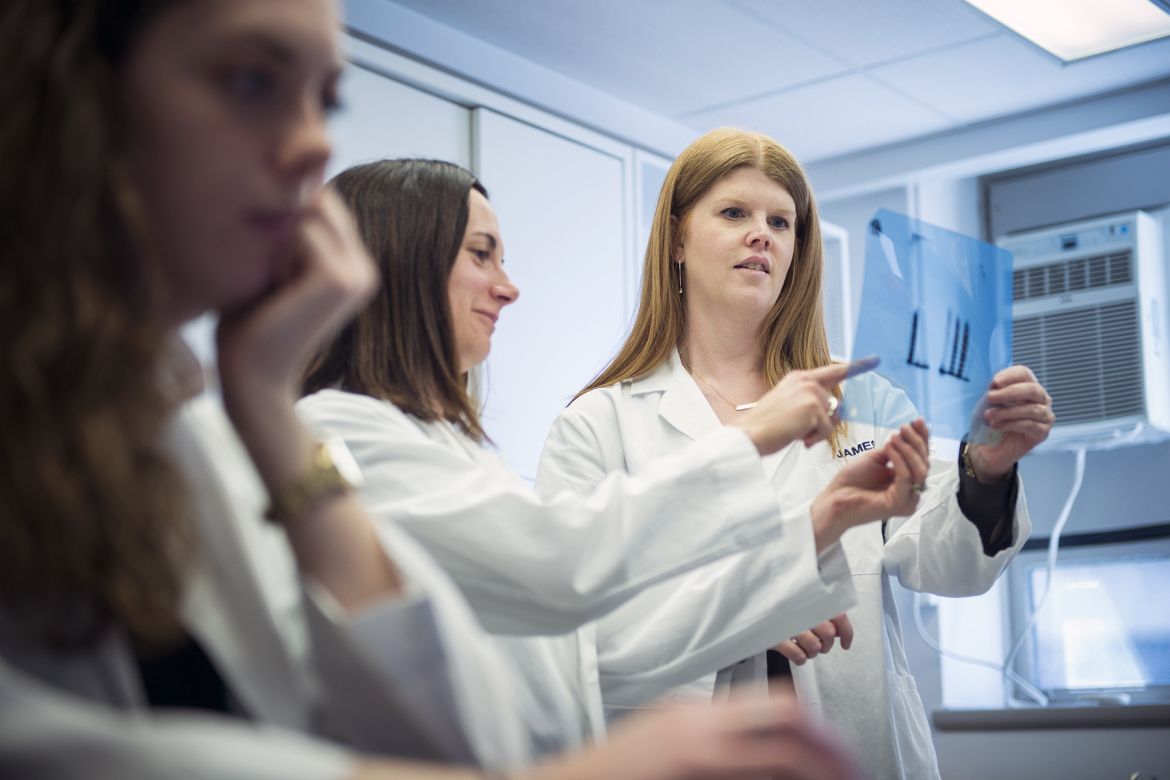

Building local expertise

Dr. James and her team are building expertise in Kingston to analyze genomic results locally, with support from specialists like Dr. David Lillicrap, Dr. Jennifer Leung, Dr. Mackenzie Bowman, Dr. Andrea Guerin Dr. Jeannie Callum, Dr. Laura Wheaton, Dr. David Good, Dr. Ana Johnson, Dr. Alyson Mahar and Genetic Counsellor Nicole Yang. The sequencing itself is done at Sick Kids and experts from Toronto include Dr. Michelle Sholzberg and Dr. Andrew Paterson. Dr. Roy Khalife is involved from Ottawa. Julie Grabell, Megan Conboy and Shari Neal are also important members of the team.

The work is also helping the next generation of researchers. Dr. James credits Nurse and TMED PhD student Megan Chaigneau as a key member of the team. “Her PhD work looks at the diagnostic and emotional impacts of bleeding disorders and the nursing perspective is incredibly important,” Dr. James says. “This work is launching her into a fantastic scientific career.”