Effective immediately masking is required for everyone when present on all inpatient units, in the Emergency Department (ED), the Urgent Care Centre (UCC), and the Children’s Outpatient Centre (COPC).

Drs. Paula James and David Lillicrap were given an unexpected honour at the annual meeting of the National Hemophilia Foundation in Chicago last month. They were named “Researchers of the Year” at the event's big awards banquet.

“It was a bit of a surprise to us, but certainly a thrill to be picked,” says James.

“It's an important recognition of the good things that are happening here at KGH and Queen's University,” adds Lillicrap. “We've been at this for more than 30 years and are now into our third generation of experts in the area of bleeding disorders.”

The U.S. organization says it chose the pair for their ongoing clinical, translational and basic studies of the two inherited bleeding disorders, hemophilia and von Willebrand disease. Both conditions prevent the blood from clotting, causing abnormal bleeding or bleeding that just won't stop.

“All of our research focuses on improving peoples lives,” says James. “That means coming up with better diagnoses as well as a better understanding of the diseases so we can come up with better treatments, and perhaps even a cure.”

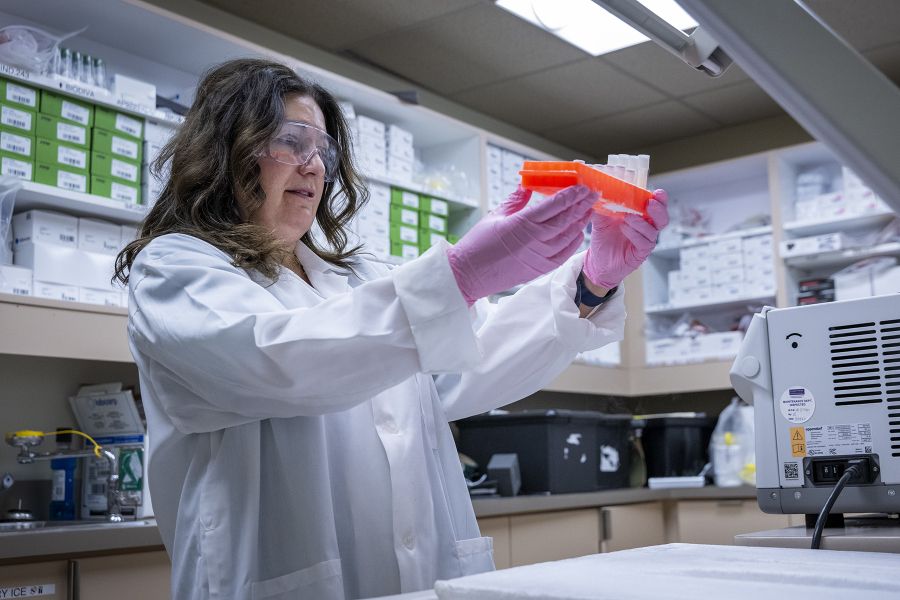

Most of their patient-focused research is carried out in two places around campus – the Molecular Hemostasis Laboratory in the Richardson Laboratory building at Queen's and the South Eastern Ontario Regional Inherited Bleeding Disorders Program here at KGH. James and Lillicrap are co-directors of both.

In the lab setting, Lillicrap is leading a team of 20 researchers who, among several projects, are working on a potential cure for hemophilia, using gene therapy. This cutting-edge science harnesses the power of viruses.

Here's how it works. People suffering from inherited bleeding disorders have a mutant gene that's causing the problem. But researchers hope to fix the problem by loading a normal version of the gene into a virus. The modified or “disabled” virus is then injected into the patient where it gets busy infecting cells. But rather than damaging the cells it instead delivers a normal copy of the gene. From there, if all goes well, the cell with start making proteins from the now normal gene and the disease will be cured.

“People have been working on this for 20 years and it hadn't worked until recently,” says James. “David's work in this area is a very important stepping stone for some exciting patient trials now under way in the U.K.”

As for her own work, James says a lot of her research is focused on helping patients with von Willebrand disease. It's not as well known as hemophilia, but affects many more people. James estimates that about 35,000 people in Canada probably have it, but only 3,500 know.

“That's because it causes milder symptoms, and the kind of symptoms it causes are things that people don't often like to talk about, such as heavy menstrual cycles,” she says. “A huge part of our research now is trying to improve and develop tools to help with the identification of affected patients.”

One of those tools is a bleeding questionnaire that will ask people about what causes them to bleed, how long it lasts, and what it takes to finally stop it.

The answers generated by this questionnaire should help more patients and primary care practitioners zero in on a diagnosis of von Willebrand disease if it's present, so treatment can begin, says James.

Lillicrap says the mix of basic research and clinical research being carried out here is unique in Canada and well known around the world.

“The things we're doing will impact the quality of diagnosis and quality of life and treatment of these patients,” says Lillicrap. “That doesn't happen overnight but over a period of time it's definitely getting better and an outright cure is certainly now possible.”