New research by Dr. Amer Johri, a clinician-scientist at Kingston Health Sciences Centre, shows that non-invasive ultrasound imaging of the major arteries in the neck may hold the key to better treatment of patients with coronary artery disease.

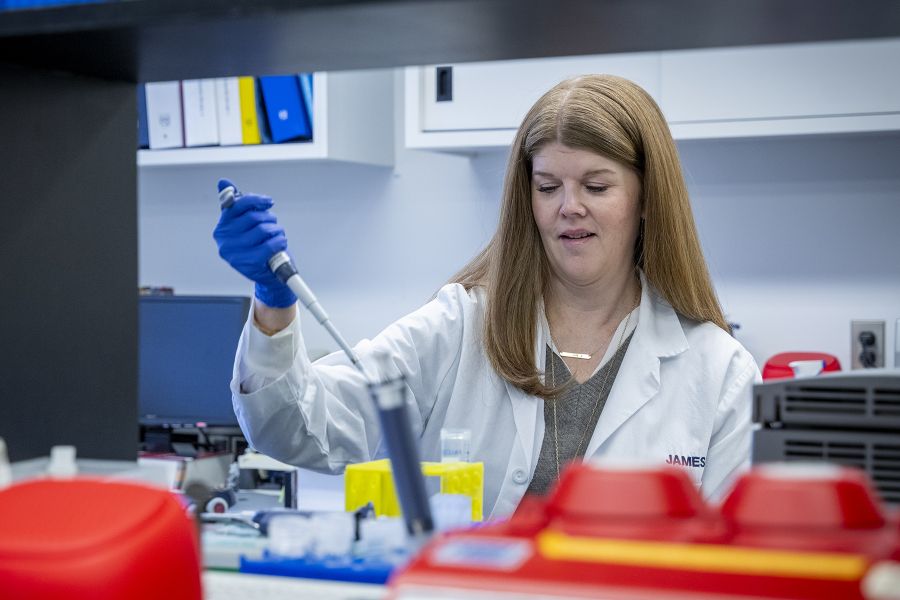

In a recently completed study, Dr. Johri,and his team used 2D ultrasound to look at the carotid arteries of 522 patients at Kingston Health Sciences Centre who also underwent angiograms for symptoms of coronary artery disease.

The researchers wanted to see whether ultrasound images of plaques, or deposits of fat and calcium, in the carotid arteries could help doctors identify patients who are at higher risk of heart attack or stroke.

One of the big challenges in treating patients with coronary artery disease is understanding how serious the disease is, and it’s hard for doctors to tell the difference without performing an angiogram.

Angiograms are an invasive procedure in which dye is inserted via narrow tube, or catheter, into a patient’s blood vessel or artery, followed by X-rays. Angiography enables doctors to see blood flow and to identify problems in the arteries leading to the heart.

“We were able to bring our ultrasound equipment right into the catheterization lab at the Kingston General Hospital site, and image the patients at the same time,” says Dr. Johri, who is also an associate professor of Medicine, Queen’s University. Unlike the arteries of the heart, the carotid arteries are easy to access by ultrasound.

In 2D ultrasound imaging, plaques show up in different shades of grey, depending on their composition. “Knowing the plaque type is important,” Johri explains. “Soft plaque is dangerous because it is more prone to break. Hard plaque, with lots of calcium, can also predict significant coronary disease.”

Analysis of these varying shades of grey showed that both the amount and the type of plaque in the carotid artery could help predict whether a patient had significant coronary artery disease.

“We found that in particular, the amount of calcium in the carotid plaques, combined with the height of the plaque, were good indicators of higher risk events,” Dr. Johri says.

This five-year study builds on earlier ultrasound research, in which Dr. Johri and his team were the first to use 3D ultrasound to show that the amount of plaque found in the neck arteries could help predict whether a patient had coronary artery disease.

While more outcomes data is needed, using ultrasound on patients could ultimately help doctors better understand patients’ level of risk more quickly, Dr. Johri says. “It’s safe, quick and portable and could help us identify those who need early treatment, or aggressive treatment or no treatment. It could also be used with other tools, such as angiogram.”

Longer term, he sees it being used in cardiac clinics or doctors’ offices for patients when their level of risk of future coronary artery disease isn’t clear.

The study was recently published in the Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. Dr. Johri thanks Julia Herr and Marie-France Hétu for their assistance with this study.