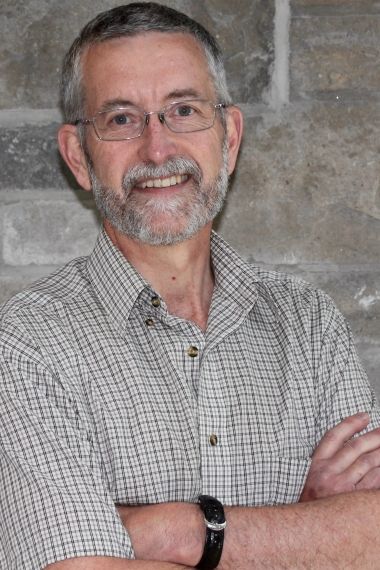

Michael Blennerhassett

- KGHRI research scientist and member, Gastrointestinal Disease Unit (GIDRU)

- Professor, Departments of Medicine and Biomedical and Molecular Sciences, Queen’s University

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal stricturing, nerve-smooth muscle interactions

Dr. Blennerhassett received his PhD from the University of Western Ontario and carried out research work at McMaster University in the areas of neuroimmunology and Intestinal inflammation before joining Queen’s and GIDRU in 1998.

His research focus is on the impact of inflammation on the enteric nervous system and how it affects neuronal survival and function. As well, there is a parallel focus on how intestinal smooth muscle cells alter their phenotype in the inflamed intestine. These interests are linked by the study of changes to the reciprocal supporting relationship between neurons and smooth muscle cells. This research is supported by NSERC.

- PhD, Western University

My research examines the effect of inflammation on the intestine, with the purpose of better understanding the effects of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in humans. For those with Crohn’s Disease (a type of IBD), the entire intestinal wall is inflamed and becomes increasingly thickened, which may cause stricturing and require surgery. My research looks at the cause of stricture formation and ways to prevent or reverse this process.

Our recent work has shown that the deeper layers of the intestine containing the enteric neurons and smooth muscle can be irreversibly affected by inflammation. For example, the smooth muscle grows, and the nervous system has to expand in parallel, but is also damaged. We propose that the growth of smooth muscle also means the release of a protein called Glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) that helps the neurons to survive and extend axons to stimulate their target tissue (the smooth muscle). Furthermore, if the smooth muscle keeps growing (and it does in continued inflammation), it seems to lose this ability, and also changes its nature in a way that keeps it proliferating even more.

Having a better understanding of how this physiology works enables us to investigate the changes seen in inflamed tissue, and look at ways to prevent or reverse the events that lead to stricture formation.