When Dr. Jeannie Callum, hematologist and transfusionist, joined Kingston Health Sciences Centre (KHSC) last year, she was pleased to learn that her new colleagues working in anesthesia, cardiac surgery and the blood bank were looking to find a way to better guide therapy for patients with abnormal bleeding following heart surgery. It is an area of expertise for Dr. Callum that she co-investigated years earlier as part of a research trial involving 12 Canadian hospitals.

“Dr. Callum’s experience at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto provided valued insight for us, as we adopted an innovative approach to rapidly measure the formation of blood clots and clotting time right in the OR,” says Dr. Michael Fitzpatrick, KHSC’s chief of staff. “The result is better informed and faster decision-making during surgery by our care teams, which should lead, ultimately, to better outcomes for our patients.”

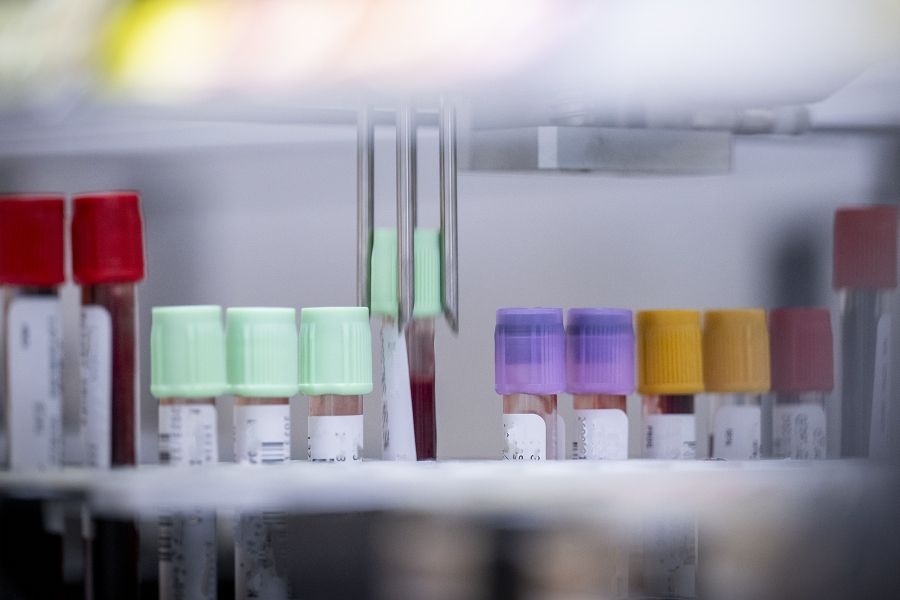

Since October, technology typically found in a laboratory is now being used in the operating room (OR) and is helping to detect whether bleeding from blood vessels will stop as expected, or if special treatment is needed to prevent a major bleeding episode and the need for a blood transfusion.

“The blood’s inability to clot is a significant complication that accounts for the majority of all transfusions of blood products in heart surgery and is related to increased instances of illness,” says Dr. Callum.

During certain heart surgeries, a heart-lung machine operated by a perfusionist is used to take over the circulation of blood so that the heart can remain still. It’s not until the end of the surgery when the machine is no longer needed that the factors or proteins responsible for normal blood clotting can be assessed.

Before this new testing procedure was in place, blood was drawn in the OR and then sent to the onsite laboratory for analysis to determine which of the several stages of the clotting process might be impaired. By the time treatment was determined and administered, patients were often times already recovering in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Now, KHSC perfusionists are performing this vital-sign assessment right in the OR and are able to provide more targeted and faster management of a bleeding disorder before a patient is transferred to the ICU.

“With these faster turnaround times for testing and intervention, the goal is to reduce the units of blood products transfused, length of hospital stays and in-hospital major complications,” says Dr. Callum.

Reducing the need for transfusions for the approximately 25 per cent of heart surgery patients whose blood clotting is impaired is not only good for their health outcomes, it is also important for managing the inventory of blood products, especially for those products such as platelets that have a short shelf-life and for which there are intermittent shortages.

Gallery

KHSC perfusionists with the new equipment that allows them to assess the blood-clotting process right in the OR and provide more targeted and faster management of a bleeding disorder.

Maggie Savelberg, KHSC perfusionist, with the heart-lung machine that circulates blood so that the heart can remain still during certain surgeries. It’s not until the end of a surgery when the machine is no longer needed that the factors or proteins res