For approximately 25 per cent of patients in Kingston Health Sciences Centre’s (KHSC) ICU with serious injury to their kidneys, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), a special type of dialysis, can be life-saving.

In December, KHSC’s fleet of CRRT machines, the only ones available in southeastern Ontario, was upgraded to continue to support ICU patients from across the southeast region who are too sick to tolerate standard hemodialysis, which is a treatment that cleanses the body’s blood of toxins and excess water, something healthy kidneys do.

Standard dialysis is done over four hours, while CRRT is done over several days to slowly and continuously clean out the waste products and fluid from a person’s body.

CRRT is used most often for patients who suffer acute kidney injury (AKI) from a traumatic injury, illness, severe infection (sepsis) or medication reaction.

People who need CRRT receive it through a catheter placed in the neck or groin. The catheter is connected to the CRRT machine. During the therapy, the machine slowly pumps blood from the body, filters it, and pumps purified fluids back into the body.

Not only do the new machines improve treatment accuracy with features such as intelligent pump adjustments that make it easier to meet fluid removal targets prescribed by care teams, the machines have also been designed to offload some of the cumbersome tasks the old equipment required staff to perform.

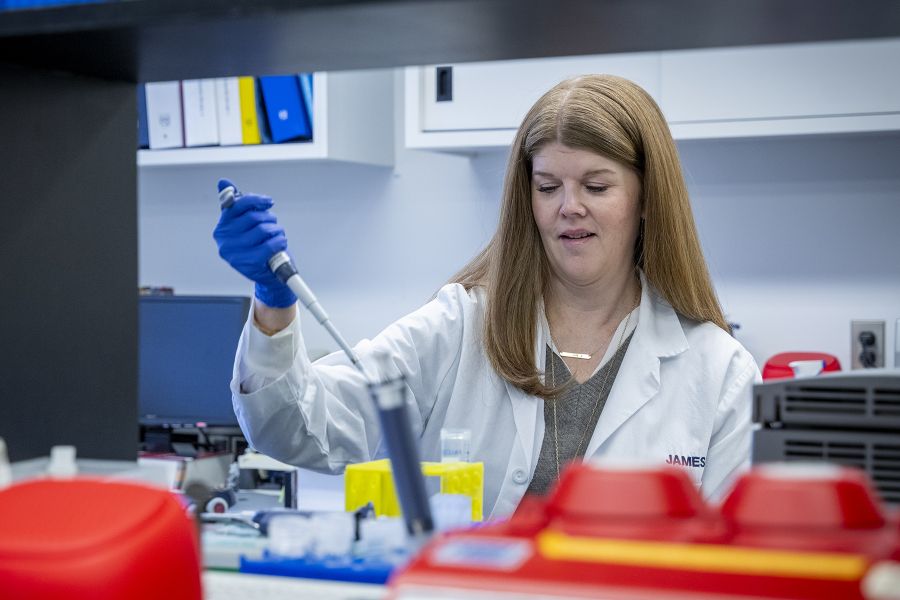

“An auto-waste feature eliminates the lugging of five-liter bags of waste several times in a shift to the physical drain in the wall that can be across the room,” says Stephanie Sorensen, a clinical learning specialist who supported the Kidd 2 ICU in its adoption of this new equipment, including education for 80 specialized KHSC ICU nurses.

“Care teams not only keep a close eye on the functioning of the machine performing the work of the injured kidney, they must also monitor a patient’s body fluids, response to therapy and vital signs during treatment,” adds Sorensen.

AKI is a common complication of severe critical illness and rates are on the rise. Over the past three years, the number of KHSC patients with AKI has increased 27 per cent.

These new machines will allow KHSC’s specially trained ICU nurses to support the kidney function of the over 100 KHSC patients each year who experience AKI during their critical illness, in the hope of reversing AKI.