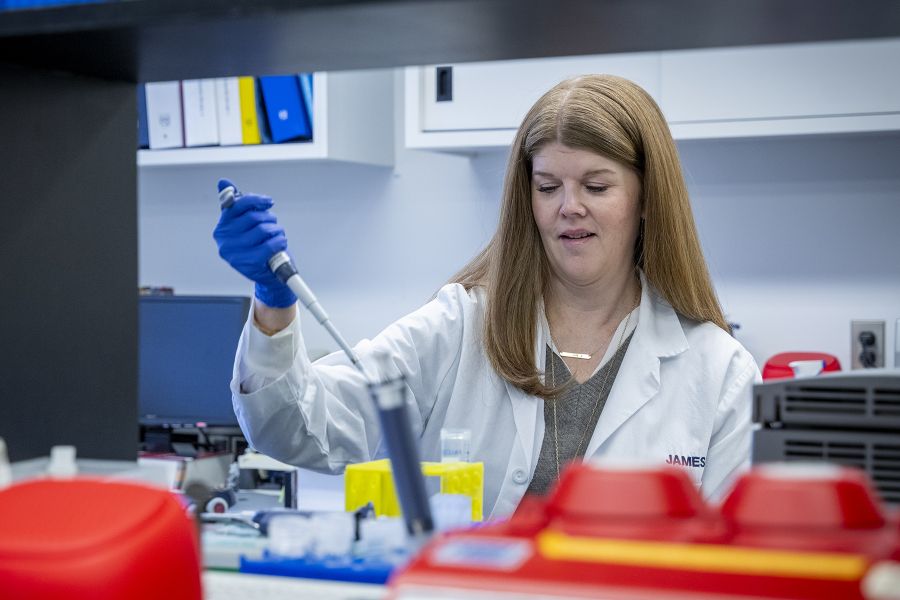

Joanna Hearn is one of nearly 40 patients living with epilepsy who are receiving care from Kingston Health Sciences Centre (KHSC) teams to make sure their implanted vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) devices are delivering electrical impulses to the nerve at the appropriate duration, frequency and intensity to help control seizures.

Since 2021, KHSC has been approved to have Dr. Ron Levy complete eight VNS implants per year. The vagus nerve runs from the base of the brain along both sides of the neck, through the chest and down to the colon. It helps control actions that happen automatically, such as breathing, digestion and heart rate, and appears to be important in regulating seizure activity.

“While VNS is not a cure for epilepsy and it does not work for everyone, it can help some people experience fewer, milder seizures,” says Dr. Lysa Lomax, medical director of the District Epilepsy Centre at KHSC. “People whose seizures are not well-controlled with medication and are focal, occurring in one area of the brain, are those who may benefit the most from stimulation therapy.” Thirty per cent of people with epilepsy cannot achieve seizure freedom with medications or specialized brain surgeries.

Hearn needed to travel to London, Ontario to get her implanted device while KHSC worked to implement its VNS program, but is now able to be monitored here in Kingston along with approximately 20 other patients who previously travelled to Toronto, London or Montreal to receive their devices.

“It’s great this treatment option is now more accessible for people in the southeast,” says Hearn, who was diagnosed with epilepsy in 2009 and has received all of her epilepsy-related surgeries outside of Kingston. Today, surgeries such as resection surgery, involving the removal of small portions of the brain where seizures occur, are performed regularly at KHSC.

Hearn takes medication she says helps her control generalized seizures, which occur throughout the brain and can cause a person to lose consciousness and fall to the ground. She first learned about VNS from Dr. Lomax during a conversation about the absence of her generalized seizures since 2019 as an option that could help with the focal seizures that continued to occur on the left side of her brain.

“I trust her judgment and decided the risks were worth the possibility of a better quality of life,” says Hearn. “I would say my focal seizures are less intense and I recover from them more quickly since having the implant. I’m also having seizures I don’t notice but the device records.”

One of the possible side effects of VNS is worsening sleep apnea. Because Hearn has a history of sleep apnea, she had a follow-up sleep study during a stay in KHSC’s Sleep Lab with her service dog Lucy.

“It meant a lot to me to have Lucy with me overnight in the Sleep Lab – I don’t go anywhere without my service dog,” says Hearn. Lucy, who is trained to respond to seizures, recently retired and continues to live with Hearn. She has a new service dog named Joey, a chocolate Labrador, who will receive similar training.

Should Hearn decide she no longer wants to use the implanted stimulator, it can be removed or switched off.

VNS devices for epilepsy are surgically implanted under the skin of the upper left side of the chest with a wire threaded under the skin to connect the device to the vagus nerve on the left side of the neck.

Patients typically go home the same day of surgery and after the stimulator is programmed by an epileptologist (a neurologist specializing in epilepsy) to turn on and off in cycles such as 30 seconds on, three minutes off. The device also stimulates the nerve when there is a rapid increase in heart rate, which may indicate a seizure.

Generally, the length, frequency and intensity of the stimulation starts at a low level and is gradually increased depending on a patient’s response to the device.

In the beginning, Hearn found it painful and had a sore throat until her body got used to it. It took about 12 weeks before her device was adjusted to provide increased stimulation.

She continues to have a hoarse voice when the device is on, which can be a problem when Hearn wants to sing. She loves singing choral music, so, fortunately, she has a workaround. Her device came with a hand-held magnet that allows her to temporarily stop the device while she belts out her favourite songs. She can also use the magnet to turn it on if she senses she is about to have a seizure.

Despite epilepsy being one of the most common conditions affecting the brain, around 5000 people in southeastern Ontario live with the condition, Hearn says living with epilepsy can feel lonely. For her, the online and in-person art workshops offered through Art for Epilepsy (Facebook page) are a creative outlet and connect her to a community of people with epilepsy.

She also encourages the general public to learn more about what they can do when someone has a seizure in a public place. First aid advice such as staying calm, creating a safe space and knowing when to call 9-1-1 is available at Epilepsy Ontario.