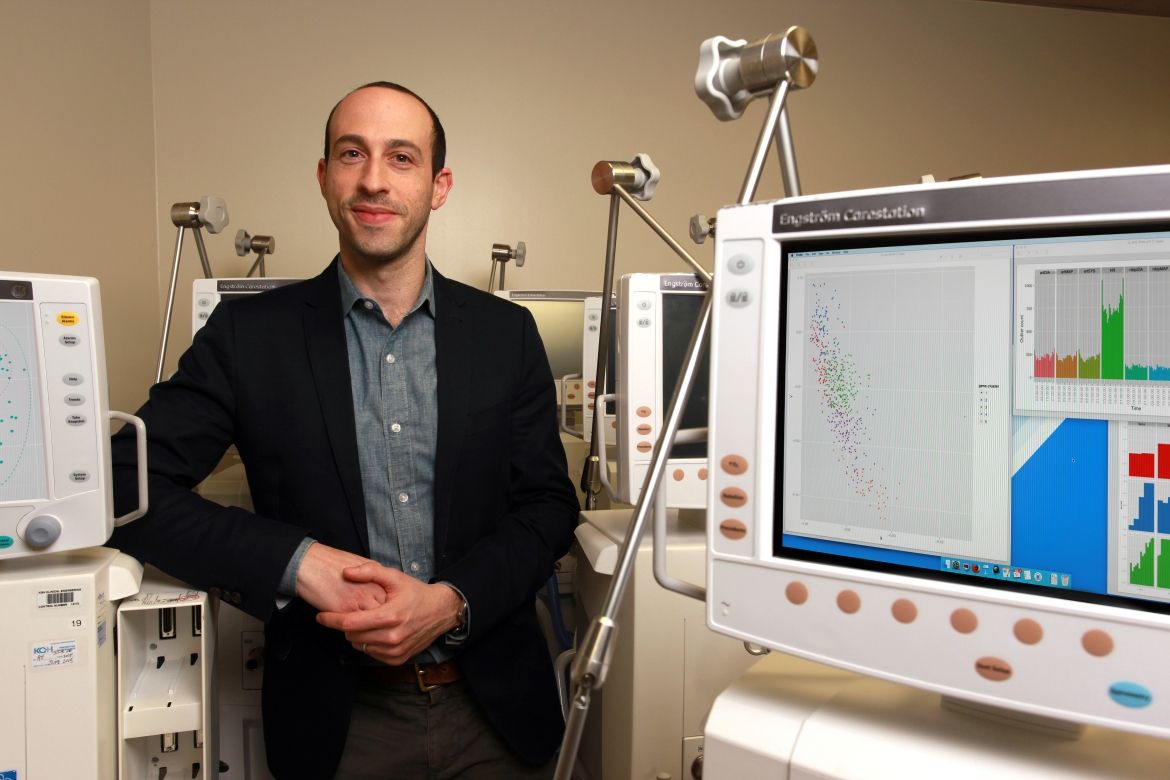

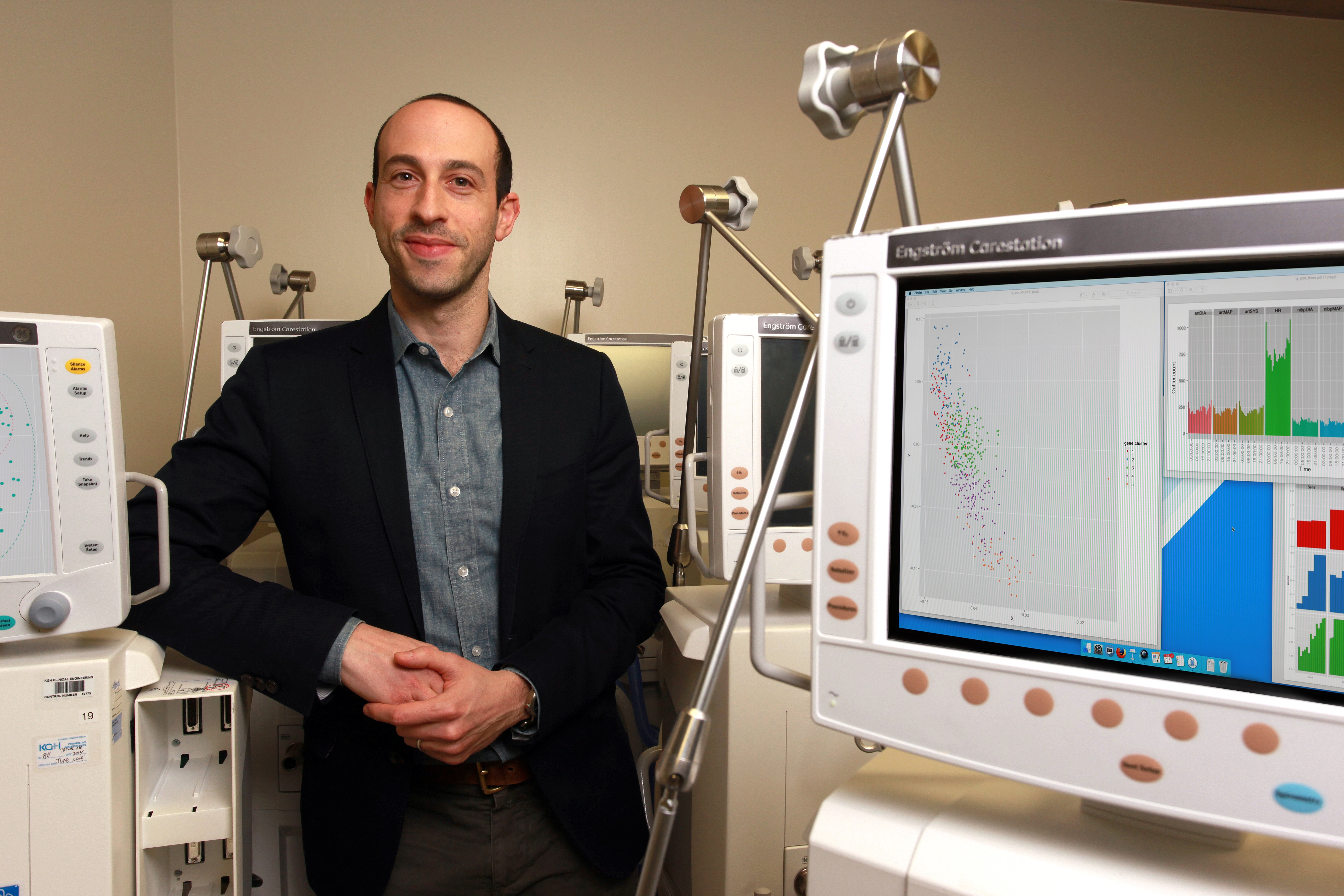

David Maslove, a clinician scientist and intensive care specialist with the Kingston General Hospital Research Institute, has published new research that suggests that commercially available fitness trackers provide accurate enough data to be useful for patient monitoring in a hospital setting.

With the increasing popularity of personal fitness trackers – particularly those capable of monitoring activity levels, heart rate and even sleep patterns – many have wondered whether these devices could be useful in a formal medical setting. The study found that, despite some difficulty in measuring heart rates for those with irregular rhythms, the data captured by fitness trackers was within a few beats per minute of that measured by a gold-standard continuous electrocardiograph (cECG).

“There has been talk in the medical literature about the increased functionality of personal fitness trackers and whether they would be useful – and accurate enough – in a healthcare environment,” says Dr. Maslove, who is also an assistant professor in Queen’s University’s Department of Medicine and Critical Care Program. “There wasn’t a lot known about how they can be used and whether they can provide robust enough data. Because we’ve got the capability of collecting gold-standard heart rates from patients in the Intensive Care Unit, that would be an opportunity to study the accuracy of fitness trackers in a healthcare setting.”

Along with colleagues Ryan Kroll and J. Gordon Boyd, Dr. Maslove collected heart rate data from 50 stable Intensive Care Unit patients, using both a cECG and a commercially available personal fitness tracker. Patients were monitored for a full 24-hour period using both devices.

For patients with a normal heart rhythm, the fitness tracker reported a heart rate that was, on average. 1.14 beats per minute (bpm) below the cECG measured heart rate, with 73 per cent of readings within 5 bpm of the cECG measurement. The study did find a tendency for trackers to report less accurate data for heart rates between 75 and 120 bpm and to report slightly more inaccurate data for patients with irregular heartbeats.

“We were pleasantly surprised by the results, which showed that for most patients the devices seemed to work well,” says Dr. Maslove. “There have been a number of negative media stories about the purported inaccuracy of these devices, but these results seemed to resonate with the experiences of other colleagues, and are now supported by that gold standard validation.”

Dr. Maslove says the next step will be to conduct more rigorous research on how the devices are best used in a hospital setting – determining in which populations the devices are most effective, how best to use the technology in its current form, and what features or capabilities would improve their utility. Given the comparably low cost of the devices, he says, further studies could examine the feasibility of sending patients home with the devices and collecting data from them at home. Such an intervention could allow a provider to respond proactively rather than waiting for the patient to return to the hospital if issues arise.

The study, Accuracy of a wrist-worn wearable device for monitoring heart rates in hospital inpatients: A prospective observational study, was published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research.