Palliative care and end-of-life issues have been headline news recently. Our aging population and the resulting strain on our health care system are raising questions about how and where we provide care. The proposed medically assisted dying bill has provoked a national conversation around what’s important to us and how we want to face the end of our lives.

Many of us are living with these issues, caring for ailing or aging family members or friends, or dealing with our own frailties, be they lingering injuries or life-limiting illnesses. The journey can be long, lonely and painful, both for patients and their caregivers.

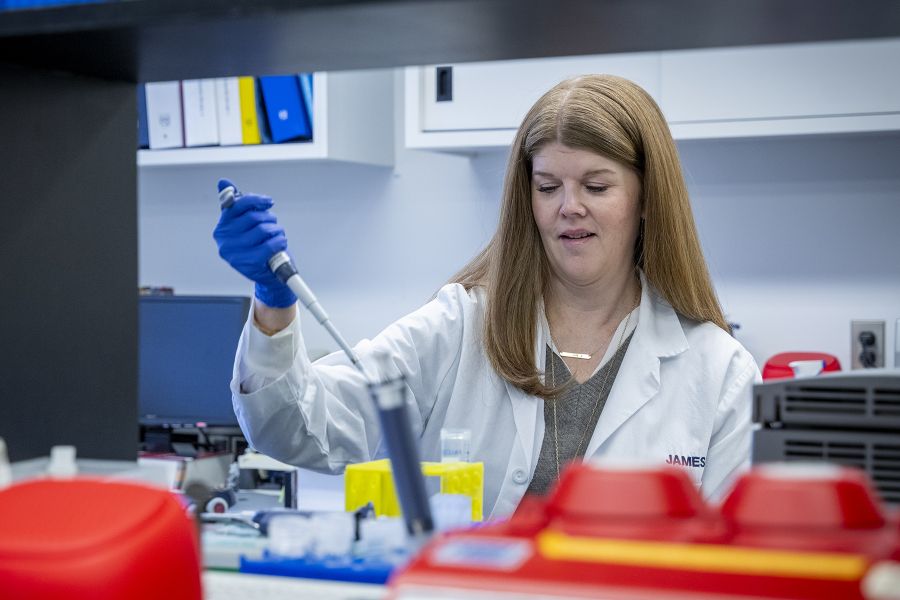

At the Kingston General Hospital Research Institute, our clinician-scientists have been studying aspects of end-of-life care for over 20 years. Their findings are being translated into vital policies, tools and best practices for guiding how, when, and where we die.

Dr. Daren Heyland, Director of the Clinical Evaluation Research Unit at KGH, has dedicated much of the past two decades to understanding and documenting the quality of care given to the critically ill, and the need for families and medical practitioners to talk about end-of-life care. As Director of the Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET), he has, with others, conducted several studies that have revealed important information about end-of-life-care and our health care system: For example:

- The CANHELP study surveyed patients and families about aspects of care that were important to them at the end of life, and how satisfied they were with how this care was delivered. Researchers found that the location of care was very important, as was communication, and avoidance of unnecessary treatments such as life support;

- The ACCEPT study, which looked at how wishes for care were communicated, found that patient preferences for care were reflected in their care charts only 30% of the time; and

- The DECIDE study, which examined end-of-life discussions from the health professionals’ perspective, found that health professionals felt that patients and families had difficulty understanding and accepting their love one’s prognosis.

Dr. Heyland was also involved in developing a national framework for advance care planning, a process for reflecting on and communicating one’s wishes for care, and he was part of the creation of the national Speak Up campaign for advance care planning (advancecareplanning.ca).

A related and often overlooked topic is palliative care. Inside our hospital, a project to improve palliative care for patients with life-limiting illnesses has led to a unique research study on palliative care that engaged former hospital patients or their family members in both developing the study and conducting interviews with patients and their caregivers on their needs and wishes for care. While results are pending, an important lesson has already been learned: that patients’ perspectives are important, not just as research subjects, but as active participants throughout the research process, including study development.

In tandem with this study, KGH, Providence Care and the South East Community Care Access Centre have received funding from Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvements (CFHI) to develop systems and practices to improve access to palliative care.

Nationally, The Canadian Frailty Network, led by KGH critical care physician John Muscedere and headquartered here in Kingston, supports research and knowledge translation leading to better care practices for the frail elderly. For example, a recent study into lifelong medications for chronic conditions showed that elderly patients and their families support stopping non-comfort medications that have no clear benefit to the patient. This is but one of a broad sweep of studies being carried on across more than 200 institutions and organizations across Canada, offering solutions, policies and best practices leading to better quality of care for the frail elderly.

Aging, ailing, and death are uncomfortable topics to contemplate. But thanks to the efforts of our researchers, caregivers and patients, we’re learning new and better ways to respect and protect the well-being of those who are approaching the inevitable. As we all are.

Roger Deeley is Vice President, Health Sciences Research, KGH, and President, KGHRI.

This blog post originally appeared on the Council of Academic Hospitals Healthier, Wealthier, Smarter website.