A new approach to treating grass allergies offers potential as a shorter and more effective alternative to traditional allergen immunotherapy (a.k.a. “allergy shots”), a study led by KGHRI clinician scientist Dr. Anne Ellis has shown.

It was the first-ever completed Phase II study using synthetic peptides to treat a grass allergy. One of the largest ever conducted on this allergen, the Phase II clinical trial looked at the effectiveness and safety of a grass peptide-based immunotherapy, compared to a placebo, in 226 study participants.

For many Canadians, the misery of grass allergy season can be lessened through allergy shots. But this well-known treatment not only involves the discomfort of weekly needles for four to six months, followed by monthly injections for up to 5 years after, it also carries a not insignificant risk of severe reactions, including anaphylaxis.

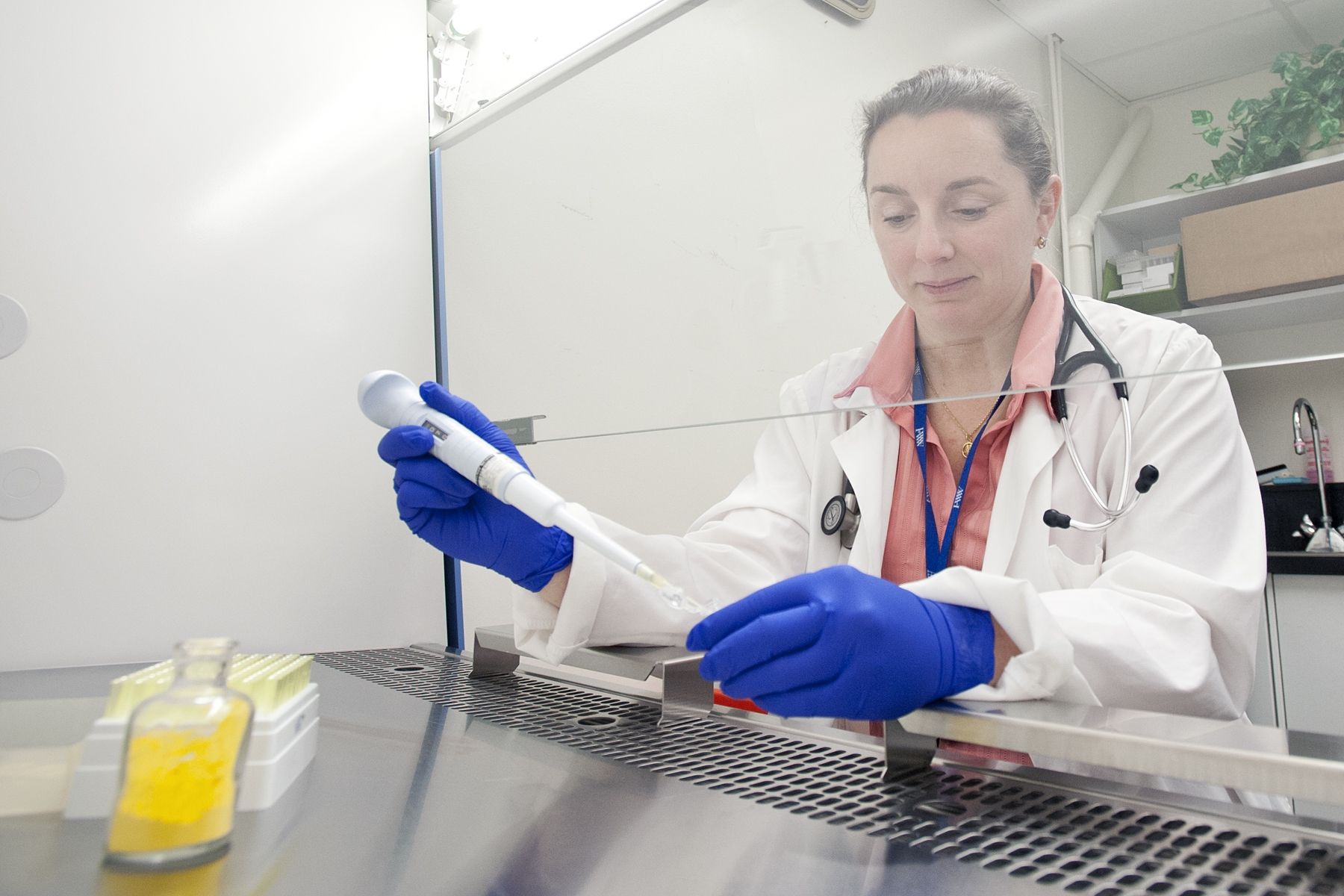

Participants chosen for the study were treated with either the peptides or a placebo four months before grass season. After just 8 injections (given every 2 weeks) for 14 weeks in total they were exposed to grass pollen in the Environmental Exposure Unit (EEU) at Kingston General Hospital, a state-of-the-art controlled environmental exposure facility that enables up to 140 participants to be tested at the same time.

Dr. Ellis’s study showed that participants who received the peptide treatment showed a significant reduction in allergy symptoms such as sneezing, nasal congestion and runny nose upon exposure to grass pollen, while avoiding serious reactions such as anaphylaxis.

Also known as SPIREs, synthetic peptides are showing promise as a better alternative to treat allergies than traditional vaccines, says Dr. Ellis, who is also an Associate Professor in the departments of Medicine and Biomedical & Molecular Sciences at Queen’s University.

Unlike traditional grass allergy injections, which use all of the proteins from grass, this kind of therapy works through a different mechanism, using tiny bits of specific proteins to target the most important immune cells, says Dr. Ellis. “It’s a new way of giving immunotherapy that bypasses the indirect route of traditional treatment and goes right to the most important effector cells. The theory is that the proteins used in this kind of therapy are so small, they avoid anaphylaxis,” she says.

The study also showed that this treatment could be done over a shorter period of time – one dose every two weeks over 14 weeks, compared to the nearly year-round frequency of traditional allergy shots.

Interestingly, a higher dose of the peptide treatment, delivered over four-week intervals, was no more effective than the lower dose given biweekly. “We saw the same thing in studies using synthetic peptides for allergies to cats and dust mites,” Dr. Ellis says. “It’s clear that immunotherapy using these peptides is different – it causes a bit of a rethink about how the immune system works.”

Dr. Ellis’s study was published this week in the prestigious Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. It was also highlighted in the “Latest Research” section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology website.