Researchers at Kingston Health Sciences Centre and Queen’s University have published the first set of findings stemming from the Kingston Allergy Birth Cohort – a study that tracks the origins of allergies in nearly 400 mother-child pairs from pre-birth into early childhood.

The study confirmed a number of previously known factors that play a role in the development of respiratory symptoms. It also uncovers a new link between air fresheners and respiratory issues.

The study examines parent-reported symptoms of respiratory symptoms – such as wheeze, recurrent infections, use of asthma medications, etc. – in the first year of a child’s life, and looks at external and internal factors that play a role in the development of allergies.

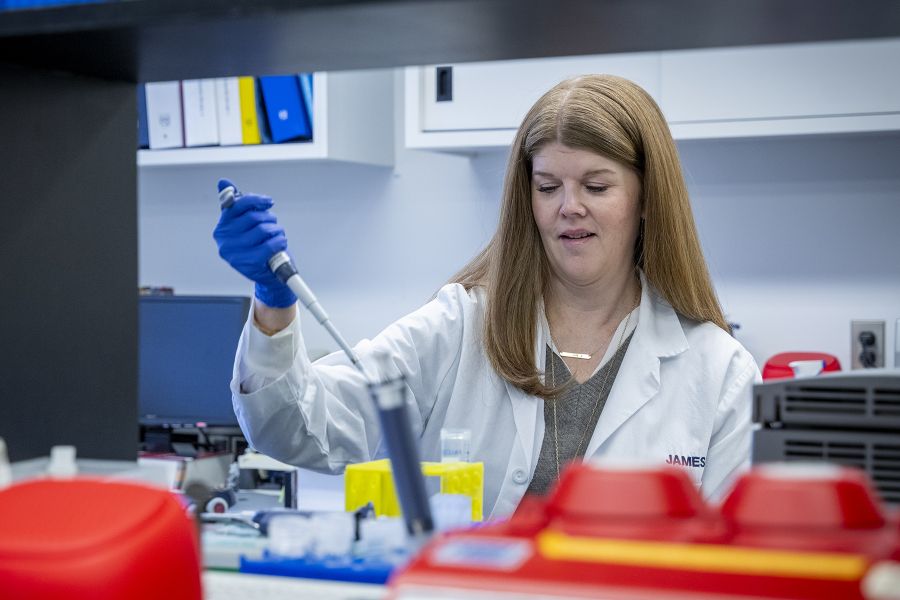

“The Kingston Allergy Birth Cohort is truly a novel experimental group,” says Dr. Anne Ellis, the study’s lead author and a clinician scientist with the KGH Research Institute. “Kingston has a number of unique characteristics – such as a rate of smoking that is above the national average, a rare mix of urban and rural populations and a wide array of socioeconomic levels. All of these factors allow us a unique insight into factors involved in allergy.”

The cohort study is believed to be the first to examine early childhood respiratory symptoms from the perspective of the exposome -- the combination of all internal and external factors that can play a role in health of a patient. These include general external factors (such as socioeconomic status), specific external factors (such as exposure to cigarette smoke), and internal factors (such as age and parental history).

Using these factors, Dr. Ellis and her team were able to determine which exposures were already significantly associated with each other and control for the factors individually to determine which correlations could be more meaningful.

The researchers uncovered a previously unknown positive correlation between the presence of air fresheners in the house and respiratory symptoms, independent of other causes. The study also confirmed a number of previously known correlations between exposome factors and likelihood of developing allergy symptoms. Exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy increased the likelihood of respiratory symptoms, while post-natal factors such as breastfeeding, the presence of older siblings or the mother being older at the time of gestation correlated with lower instances of allergy.

Dr. Ellis says the ability to follow the cohort – many of whom are now three to five years of age – through time will allow for a more thorough understanding of the factors contributing to allergy development. Further studies involving the cohort group are underway, using skin tests to identify allergies, as well as in-home investigations.

“This is the first real feedback we have for the participants in the Kingston Allergy Birth Cohort,” explains Dr. Ellis. “There are so many other factors that can contribute to the development of allergies. With the approach we used in the cohort, we’re able to account for general external factors, specific external factors and internal factors that can contribute to the development of allergies so that we can whittle it down to what’s truly significant.”

The full study, titled The Kingston Allergy Birth Cohort, Exploring parentally reported respiratory outcomes through the lens of the exposome, is available online from the Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

Gallery

Dr. Anne Ellis is the study’s lead author and a clinician scientist with the KGH Research Institute